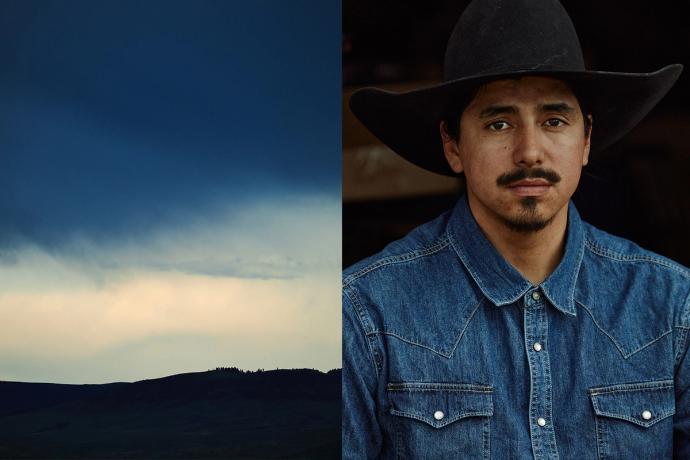

At 30 years old, it doesn’t make sense that Stephen Yellowtail III should lead with the gratitude and humility of weathered years or that he should so readily defer praise to the teachers and mentors he’s had along the way. After all, the strain has always been his to bear. But Stephen Yellowtail III knows that going gently for the things you care about is not an option. While he may be a man of few words, the ones cowboy and fourth-generation Crow Nation rancher Stephen Yellowtail chooses are important.

Stephen was born on December 11, 1993, to parents Lena and Wailes Yellowtail, in Crow Agency, Montana. The third of four children and the first son, he recalls a loving family home, fertile ground for the seeds of heritage, family, stewardship, and compassion that would take root in the observant, insightful boy. He spent most of his childhood “cowboying it up,” learning all things horses and cattle, bareback racing his friends, and aspiring to become the relay riders and warriors of old. “There was a healthy competitive spirit in everything, whether it was the friendly jabs at attempting to master too much horse, the roping and racing, or the basketball games later on,” smiles Stephen.

He attended school at Tongue River — just off the Reservation and across the state line between Ranchester and Dayton, Wyoming — because his parents wanted him and his siblings to know life and culture “off the rez,” to be able to flourish in the world, no matter where they landed. “Tongue River was an amazing school system,” remarks Yellowtail. “They all wanted to see me succeed. Good teachers, mentors, are so important; the love and support they showed me in the classroom has influenced my entire life.”

Yellowtail spends a good deal of time considering the impacts of the Tongue River school system — and the teachers that would come after — on his trajectory in life, particularly as he contemplates their lack for so many children today. “I see a lot of kids that don’t have adequate role models or the parental supervision they need. No one tells them they’ve done well at anything as a child, they’ve never had that affirmation. A child is just like a young horse,” explains Yellowtail, “they have wants and needs that must be met and they require guidance, but not in a way that’s going to scare them. That one person, taking just a brief moment to listen and support can mean everything, it can move that child forward toward hope.”

As it did for Yellowtail. The support of his parents and Tongue River drove him ever onward. He excelled in school, eventually becoming the student body president. And the basketball team leader. Observant and analytical, naturally athletic and self-driven, Yellowtail dominated the court, studying his opponents for weaknesses, finding holes in their game, and counting coups in the only way left to a contemporary Crow warrior. He continually surrounded himself with those who were better — playing against high school boys in middle school, and against college crews in high school — always watching, striving for more, aiming higher. “I had a responsibility to the schools and my parents,” says Yellowtail. “I’m the result of the love and compassion that they’ve shown me. Even now, it’s never just Stephen Yellowtail that I’m representing. I represent my dad, my grandfather, and the hard work they went through to get respect from non-native communities. I’m what’s come before and what’s to come.”

Though he had no intention of continuing to play in college, he had what it took and was heavily recruited by the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology to play Division II. A trip full of scrimmages with the team and meetings with the various engineering departments, particularly industrial engineering professor Dr. Carter Kerk, solidified his educational future. “To this day, Dr. Kerk remains one of the most influential men in my life. If I called him right now and said I wanted to go to graduate school, he would make time for me. By the end of the day, he would probably send me a list of leads and a letter of recommendation,” laughs Yellowtail. “My success in college and my character comes from him; he was, and is, an incredible man.”

Despite his academic success, Stephen felt a calling back to the land and a legacy begun with his great great grandfather and the family’s (sur)namesake, Hawk with Yellowtail Feathers, who first farmed the plot under the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887; with his great grandfather, Carson Yellowtail, who was gifted by his neighbor as many half-frozen calves as he could save in the aftermath of the great blizzard of 1919 to start the family herd; and with a purpose that knew his name before he was even born. So, he returned to the unspoken communion with his horses, the insistent negotiations with stubborn cattle, and the breaking of dawn you can almost hear over mountains and prairie expanses that deafen with their presence. For several years out of college, he spent the summers with his father handling their 350-head herd on their 12,000-acre family ranch in Wyola, Montana, and his winters roping heavy, riding, and training in Wickenburg, Arizona. “I’m the only one of my siblings still involved in the ranch,” says Yellowtail. “But this lifestyle, there’s just got to be something in your blood that makes you want to do it, to get up at 2 am in the middle of a blizzard, when you’re tired and cold, to save a life.” Eventually, he remained year round and settled into the rhythm akin to his own heartbeat or a drum —steady and sure.

In this, perhaps, is everything. Ranching, accepting the role of steward over the creatures and land, is more intimately connected with the Indigenous narrative, with the blood, than anyone might readily consider. “I almost think of our ranching heritage like our cultural heritage: I need to protect it.” Whether the threat is financial or physical, from within or without, both legacies are struggling for solvency and sovereignty. “Whenever you have livestock, you’re going to have dead stock: there are just so many things out of your control,” Stephen remarks. “But, for three generations, the men in my family have protected the animals and land to provide for their families. What we have is what we’ve held onto for centuries. This ranch is where my ancestors roamed hundreds of years ago. What we take is a gift, a blessing, to be honored. Animals aren’t here just to feed us: that animal sacrifices its life to feed my family, and I have a responsibility to respect that sacrifice. It’s a lot like ranching: I’m just here to take care of it. If I take care of those cows, they’re going to take care of me. It’s all interconnected.”

What will that mean for Stephen’s son, Greyson, who turns two this July, or for his second son, who is due to arrive this summer? Stephen’s dad always pushed his children away from ranching, away from the stresses, “protecting [them] from a journey” defined by hardship. “But I was just stubborn enough,” laughs Stephen. “With my son, my children, I just want to love them no matter what.” When his girlfriend Chelsey returned to work as a night duty emergency room nurse after Greyson’s birth, Stephen gladly took the reins with his son’s care. “It was a really big blessing for me to spend that much time with my own son, so many men miss that, choose to miss that,” remarks Yellowtail. “At two-and-a-half months, he was with me in his little carrier, feeding cows. That’s his first sound, of a cow mooing; his first sights — those of cowboys, roping, camaraderie, laughter, people helping each other. You don’t teach kids, they observe, watching you.” Whatever the future holds for Greyson (and, eventually, his younger brother), Yellowtail insists the choice be his, but “so far, he loves the ranch.”

For now, the cows are calling. As summer bursts forth in Montana, things need to be done, and it’s a “dark to dark” kind of life. Up at 2:30 am, coffee and egg sandwich in hand, Stephen heads out to the barn, guided by a headlamp, to catch a horse in the dark and get the cattle done before the heat of the day hits. Only the steady thump of hooves and the tinkle of spurs — like vestiges of the heavy foot strike and jingle of ankle bells in the traditional Crow Hot Dance — accompany Yellowtail’s ride to the top of the ridge, where he might pause, for a moment, to watch the sun come up.

For more on how Stephen Yellowtail III and more from those who brought you this story, visit:

Words by Jessica Byerly - @evil_red_pen

Photos by Ian Mahathey - @ianmahatheyphoto

Featuring Stephen Yellowtail: @syellowtail